Hidden treasures, making a positive impact against all odds

Wednesday, June, 5th, 2024 News

By: Modiehi Heather Legodi

Sefako Makgatho University (SMU), South Africa

When I drove off the main tarred road, I was met by piles of garbage and dirty water running down the small streets of shacks made of corrugated iron sheets, old card boxes, plastic, etc. Zama-zama is an informally settled (slum) community located on the western side of Pretoria, comprising of about 200 stands (Picture 1). The name Zama-zama implies “those who try.” This is a community of people trying to make a living and looking for better pastures for themselves and their children.

The community forms part of outreach projects linked to a polyclinic in Daspoort, which is a clinic serviced by the University of Pretoria. The population mainly comprises of illegal Zimbabwean migrants occupying shacks that are mostly owned by South African nationals. Being an informal camp/settlement, residents don’t have access to municipal services such as clean running water, garbage removal, ablution facilities, electricity, etc.

The tiny passages and streets are also lined with people sitting outside their shacks as they wait to get informal work. Children are also seen playing in the dirty water running down the streets and on garbage-dumping sites.

This is one of the communities that the university sends student Dietitians to for their seven-week community-nutrition integrated work training block. Based on community assessment exercises conducted by students, increasing rates of food insecurity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and malnutrition were identified. The Faculty of Health Sciences Community Engagement Committee which the Department of Human Nutrition is part of, decided to collaborate on a non-communicable diseases prevention project. Participatory action research was identified as an ideal approach to implement the project with the active participation of the community members. The collaboration would also help address the community challenges in a holistic manner and ensure sustainability.

When we had our first meeting with the community members, one could see and hear the excitement that fathers, mothers, children, grandparents, and uncles had in their voices from the church songs chanted at the opening of the meeting. Even with all the limitations and challenges they have faced, the community keeps hope alive for a better life. The community also has a small garden where they grow culturally acceptable crops, located outside the mobile clinic which runs at least twice a week.

I was inspired by the willingness and excitement that the community expressed in coming up with ways in which their food access could be improved — for example, they considered a bigger garden can be started where community members can be supported with seedlings of vegetables of their choice. This would also be accompanied by education sessions on the nutritional value of culturally acceptable vegetables.

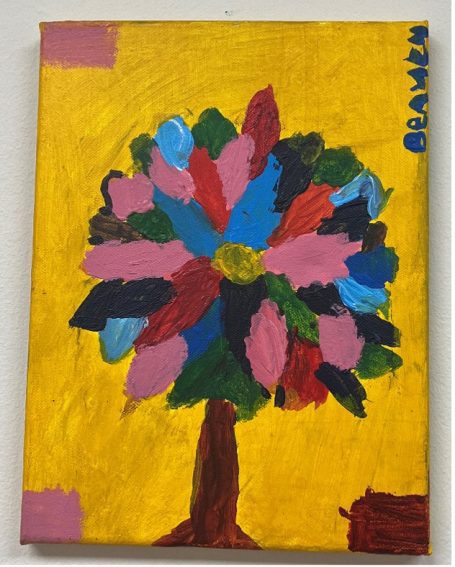

On a separate occasion, I was particularly inspired while visiting a Primary School (Banareng) in a Township called Atteridgeville in Pretoria, South Africa. It was part of a training for Dietetics students intended to expose them to surrounding communities. The school is surrounded by informal settlements. I’ve been moved to shine a light on the remarkable work being done there. During one of the visits, I bought an art piece from that school that I put up on my office wall as a reminder and for all to see. It is of a colorful tree with different fruit (picture above). It continuously reminds me of these children and their resilience, and how to see the future through their eyes despite the obvious challenges they face with no access to clean running water and safe ablution facilities within their homes.

Through the beautiful food garden planted on the school grounds, learners and community members can learn and eat from it, and they are also able to share the produce with community members who are food insecure. The school also offers music classes where learners learn to play instruments such as the violin and saxophone and they showcase their talents on national and international platforms. As researchers and academics engaging with communities, we need to be intentional about finding and partnering with such schools and similar initiatives and celebrate the hidden treasures in these communities.

It’s incredible to see how these children, despite facing challenges, are thriving, and becoming leaders in their communities. By nurturing their talents and providing opportunities for growth, educators are helping to unlock their potential and shape a brighter future for them. It’s a testament to the resilience and determination of these “hidden treasures” who are making a positive impact against all odds.