Building Up Caregiver Skills To Support People With Dementia In Bulgaria

Thursday, August, 29th, 2024 News

By: Felix Diaz

American University in Bulgaria

As I approach my seventh year living and working in Bulgaria, I am learning to understand developments in this country as essentially peripheral. Despite its long history and persistent national identity, the Bulgarian people have almost always been in between or on the side of big empires: the Romans, the Ottomans, Russia, Europe. The country has never been a substantive part of any of them for good, never at the center, never obtaining or wanting full membership – Always, though, with a pragmatic determination to continue on the margins, with little hope and enough dignity.

The current main cultural and political referent is Europe – with Russia’s influence slowly declining but still alive among the older generations. Bulgaria is gradually joining in the EU under the effect of a passive inertia force, where it is commonly assumed that this will be good for the nation for economic reasons (getting funding for projects, migrating to Central Europe) but there is virtually no active commitment to the democratic and civic values proclaimed in the EU.

When it comes to matters of development and innovation (for which people turn to Europe) versus tradition and backwardness (generally associated to the communist past), the field of disability deserves a very special chapter. It is generally acknowledged (with shy shame) that the history of attention to persons with disability in Bulgaria is one of institutional mistreatment, whereby children and adults with impairments were taken away and kept in occult, under-staffed residences in which rehabilitation and quality of life were not even considered, neglect was the norm and abuse was frequent. And, although it is understood that pro-European developments require this to change, it is also generally admitted that the needed change is coming through in clumsy, incomplete, and unsatisfactory ways.

Still, this happens in a landscape where nobody knows, and few people care, about what exactly is happening in the field of reform of services for disabled people. When in 2021 I started exploring options to build support to dementia patients in Bulgaria, my first contact was the Alzheimer Bulgaria Association (ABA). They introduced me to this scene of pervasive silence governed by a self-protective medical and administrative professional body that will often avoid responding or look in different directions when asked what is going on.

In 2015, ABA completed and published a report on national policies and practices related to dementia in Bulgaria, based on official policy documents, two quantitative surveys, six round tables and the direct experience of the Association relating to State authorities, on the one hand, and to relatives of people with dementia on the other. The report concluded with a list of needs for an integrated and adequate approach to offering proper health and care services to people with dementia, which included:

- Data collection and dissemination.

- Changing the attitudes among the relevant governmental services and institutions towards a more pro-active and cooperative approach.

- Developing mechanisms to educate specialists and train personnel.

- Developing mechanisms for supporting families in the home environment.

I initially developed my engaged research project with ABA and was inspired by these conclusions. I designed a training package for professionals to introduce, elaborate, and develop a series of assessment and intervention techniques, all of which involve close daily psychosocial support to patients. In the first phase, the Association started by arranging workshops for me with public professionals at municipalities. The target of training activities later moved from social services staff working in offices to the technical staff serving adults with disability directly. I also gradually extended my focus, from addressing intervention at elders with dementia, to a more flexible category of ‘adults with cognitive deterioration,’ which can also encompass adults with intellectual disability and elders without diagnosis.

After my first experience with Alzheimer Bulgaria, I was lucky to be put in contact with the municipality of Blagoevgrad (where AUBG is located). At the time, its Social Services team were led by a wonderful, committed woman, who made it possible to set up a wide and stable basis for collaboration with our university. She has since been replaced after the latest change in local government, but by then she had already made a notable difference in providing for the disabled and the chronically ill in the city.

The relation between AUBG and local services managed by the municipality has also been boosted by the arrival of Yordanka Trenovska in our Dean of Students’ office. Yordanka is a social worker with much knowledge about the local problematics and extensive connections in the local social tissue. All my work with local services is thanks to her and depends on her. When I leave AUBG in the following months, the University will have the opportunity to take advantage of these local connections for research, student training and social service, and take them further.

Working with professionals in the Blagoevgrad province is a direct way of accessing the reserved and unknown environment of the disabled people whose lives are sustained by residential or day-care institutions. I work with professionals at public residences for elders or adults with disabilities, including the roles of psychologists, social workers, caregivers, hygienists, nurses, and occupational therapists. Most of them are middle-aged or close to retirement, and a few are young professionals. All the professionals I have been working with are women, with the exception of a psychologist.

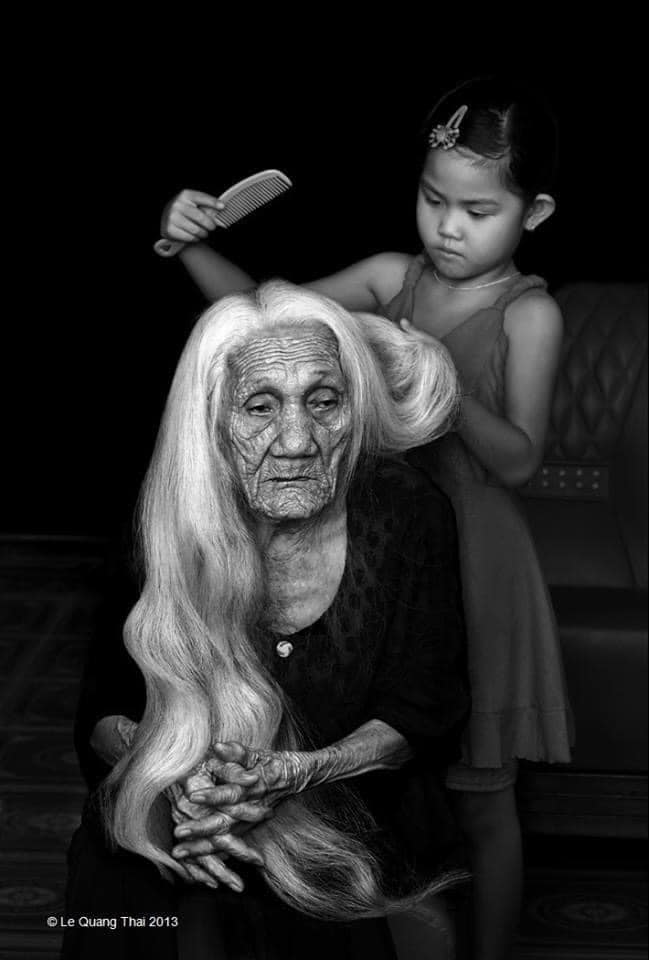

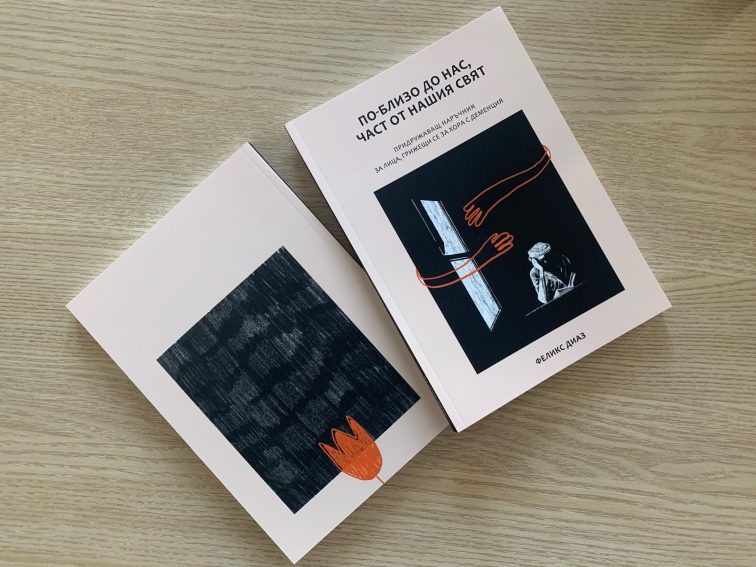

Through these training workshops, I have been extending and strengthening connections with the local professional community and, in this process, learning about what can realistically be done about disability in Bulgaria. A key landmark in this process was the publication, in June 2023, of “Closer to Us, Part of Our World,” a guidebook for dementia caregivers in Bulgarian. This book was a culmination of former training work. It compiles different traditions of intervention and concern in attention to people with dementia and it sets lines for future progress. It is meant to contribute to open pathways for further specific work, which should adjust to the needs and demands of specific professionals, collectives, and regions. My training workshops in 2024 refer to the book as a fundamental source.

I am motivated to continue opening and defining these possibilities, beyond this research project, in progressive and extensive ways. I see this process as one of disseminating a practical doctrine and well-supported practices which can only work if they are defined with sensitivity to the particulars of each place and beneficiary collective.

At the first public presentation of my book, at the municipality of Blagoevgrad in August 2023, a local journalist chose to read out loud some fragments of it, including an extract from the historical Bulgarian poem “Levski”, by Ivan Vazov. It translates to English like this:

the sweat of a simple ploughman,

the good word, the right deed,

holy righteousness boldly spoken,

the hand that is brotherly, without pride, without cry,

given surreptitiously to some wretch,

are all much nicer to God

than all the hymns and trophies superfluous